Anger Is an Illusion

An emotion is a message from the subconscious about how a fact relates to one’s values. It is not always true, but it is always a definite assertion.

Joy says that something has been gained.

Sadness says that something has been lost.

Love says that something should be sought.

Hate says that something should be avoided.

(These concepts are broader than the versions used in everyday life. “Love,” for example, refers to any degree of desire, rather than to the greatest degree specifically.)

Each emotion has a function. Joy and sadness are the ends that make love and hate possible, while love and hate are the means of driving one toward or away from what will bring joy or sadness.

If one did not enjoy sandwiches, then one could not desire them. Conversely, if one did not desire them, then one would be much less likely to walk to the kitchen to make one, even if one did enjoy them.

The four emotions already mentioned are primary. Every other emotion has the same function as one of these, only more complex.

The function of anger, for instance, is to deter threats by inciting retaliation, rather than to move one away from them directly, as simple hate would.

That this is the function of anger is clear if one compares situations that provoke it with ones that do not.

Wasting one’s money on lottery tickets does not provoke it, but robbing someone to pay for those tickets does. This is because wasting one’s money, though possible to deter, is not a threat.

Property damage caused by the weather does not provoke it, but vandalism does. This is because the weather, though a threat, is impossible to deter.

The function is not the feeling, however. Anger is for deterrence, but it is about injustice, as these examples equally demonstrate.

This raises the question of how animals experience anger.

Dogs snarl and bark to warn off threats, yet they lack the moral concerns made possible by reason, including justice.

How is anger possible without a sense of justice?

It is not—but it is possible without an objective sense of justice. In fact, it is only possible without an objective sense of justice, and this can be verified through introspection.

Imagine that someone you were playing poker with cheated, and that you lost money as a result. If you understand justice in conventional terms, then this scenario will make you angry.

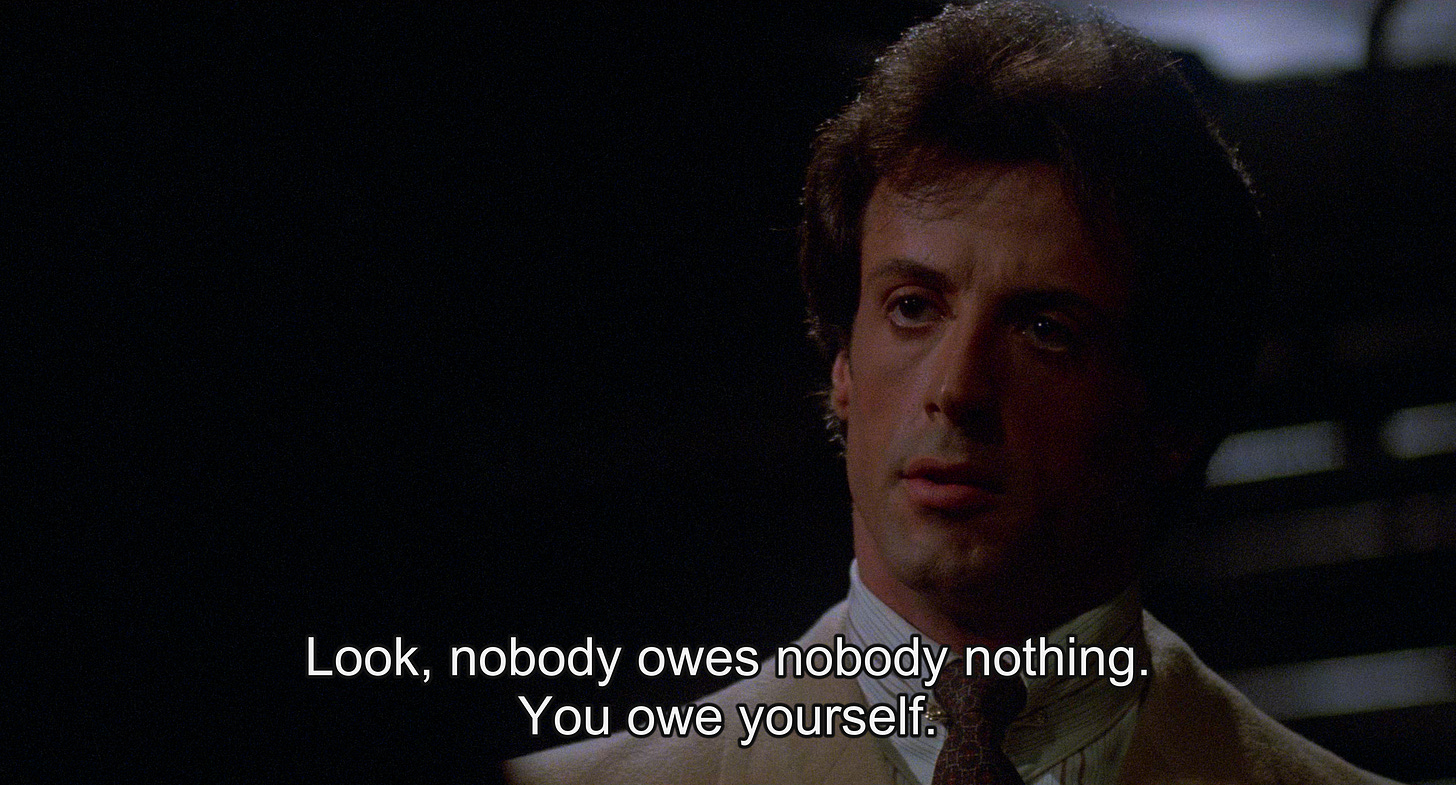

However, if you stop to consider that duty is a false concept, that the cheater has no fundamental obligation to you—even if he has one derived from what he owes himself—then you will find that your anger vanishes. You may still feel other emotions, such as disgust, but you will not feel anger.

This is because anger is not actually based on the concept of justice generally, but on the idea of intrinsic moral rights specifically.

Lacking the ability to reason, animals cannot consider alternatives beyond the perceptually apparent. This makes them largely amoral, but it does not make them robots. An animal still experiences a sense of ought in the form of its emotions.

It is the naive projection of these imperatives onto others—similar to the way that a child attempts to hide by closing his eyes—that is responsible for an animal’s sense that it has intrinsic rights, and hence for its capacity for anger.

A lion feels that it should hunt. It holds this truth to be self-evident. Consequently, when another lion infringes its territory, competing with it and making hunting more difficult, it feels that lion is wrong. When it roars, it is righteously declaring that its intrinsic rights are being violated.

No such rights exist, however. Justice is objective, which is to say that it is based on one’s relationship to others—on how one’s treatment of others redounds to oneself—rather than on some supernatural entitlement others supposedly possess.

Even though anger is false, do not feel guilty for experiencing it so long as you have not let it drive you to act irrationally. Even the most conscientious man will occasionally feel anger before he can summon the knowledge that will dispel it.

It is not even always unhelpful. It can aid one in situations that call for physical violence, which is why it exists in the first place, although in a free society—of which ours is still at least a crumbling semblance—anger does more harm than good.

It is therefore advantageous to gain some measure of control over one’s anger by recognizing that it, like the mirage of a desert oasis, is an illusion. Just as there is no water—only a misconstrued heat distortion—so there are no intrinsic moral rights—only feelings based on a false conception of justice.